"The Eve of Estes: The 1917 Hoax That Put Rocky Mountain National Park on the Map"

The Mountain Thread

Archives

"The Eve of Estes: The 1917 Hoax That Put Rocky Mountain National Park on the Map"

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

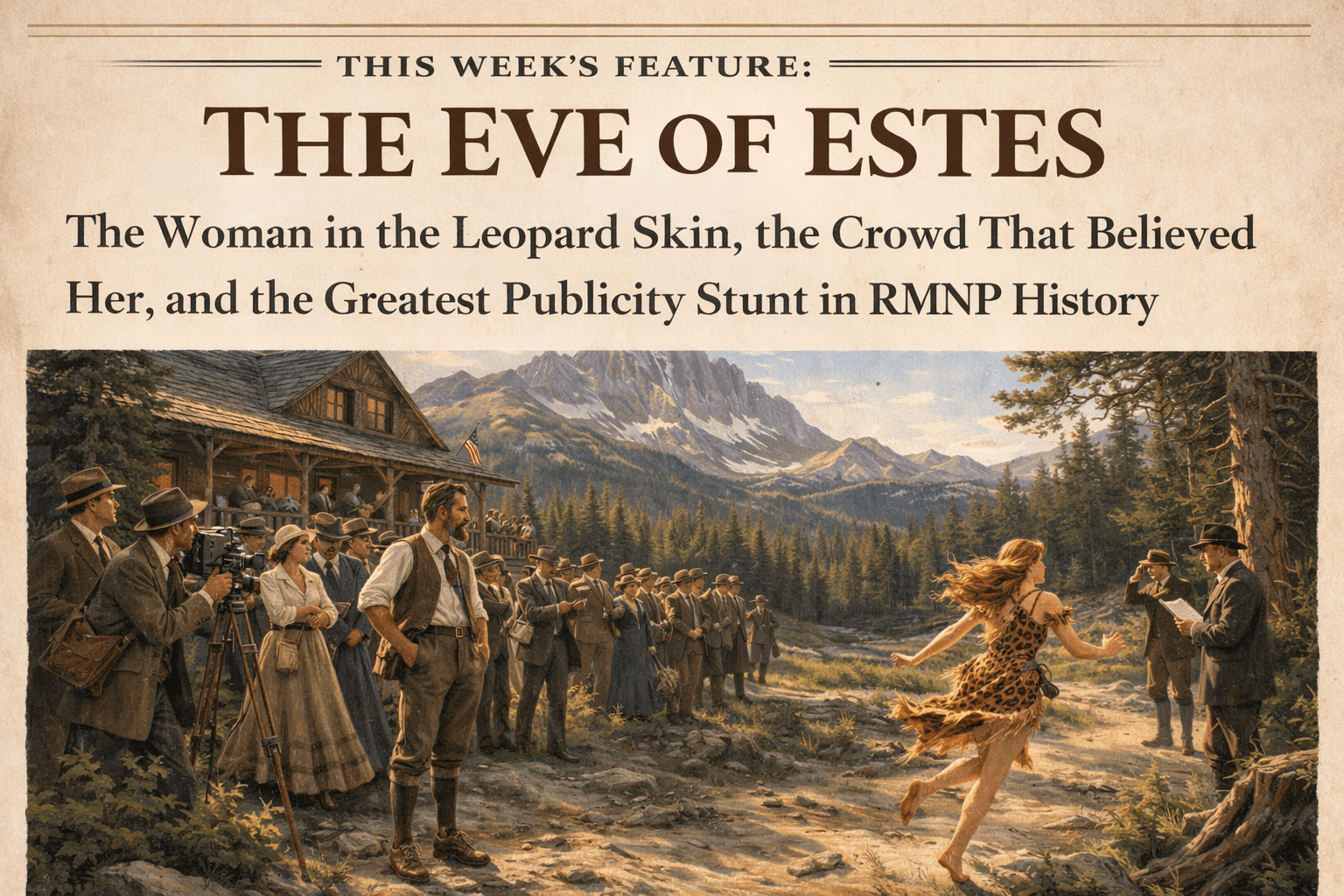

THIS WEEK'S FEATURE: THE EVE OF ESTES

The Woman in the Leopard Skin, the Crowd That Believed Her, and the Greatest Publicity Stunt in RMNP History

Rocky Mountain National Park was two years old in the summer of 1917. The mountains were spectacular. The trails were there. What the park didn't yet have was enough people coming to see any of it.

A Denver Post editor named A.G. Birch decided to fix that.

Birch was not just a newspaper man. He kept a cabin on a rocky ridge above downtown Estes Park, knew the valley and the people in it, and understood exactly what kind of story would travel across the country. He found a young woman named Hazel Eighmy working as a receptionist at a Denver photography studio. He gave her a new name. Agnes Lowe. He gave her a backstory. College student, age twenty, from the University of Michigan, fed up with the artificialities of modern city life and ready to return to something primitive. Then he called Enos Mills.

Mills was the man who had spent a decade fighting to create this park. Its most famous advocate. Its public face. The person whose name meant everything Rocky Mountain National Park stood for. On a Sunday morning in August 1917, he stood outside the Longs Peak Inn, which he owned, and shook hands with Hazel Eighmy, now Agnes Lowe, in front of nearly two thousand people. Reporters. Photographers. Park officials. Curious tourists. All of them there to watch a barefoot young woman in a leopard-skin tunic walk into the wilderness with no food, no matches, no tools, and no weapons of any kind.

Mills walked with her into the trees for a stretch, then sent her off alone toward Thunder Lake in the remote southeastern corner of the park.

The Denver Post ran her story every day for weeks.

The reports were spectacular. Agnes left messages scratched in charcoal on slabs of bark, placed on trails where rangers would find them and call in the news.

Tourists reported spotting her drinking from mountain streams, picking blackberries, and carrying a string of trout she had caught without a rod or a line. She told visitors about a run-in with a brown bear near a huckleberry patch, a sow and two cubs she had calmed by singing to them. She wrote later that no debuting soprano had ever watched an audience more carefully for signs of inattention.

Then a man from Greeley named George Desouris wrote a letter to the Post, barely spelled, declaring that a vision had compelled him to find this fair young Eve. He called himself Adam the Apostle. He showed up at the park wearing a moth-eaten bearskin. Superintendent L. Claude Way told the papers that Adam would not think he was in the Garden of Eden if he came up here.

Desouris came anyway. Agnes screamed when she spotted him and spent the better part of a day and a night running from him, including swimming across at least one body of water. It took two rangers and what the papers described as a strenuous physical altercation to remove him from the park. He was escorted out wrapped in an overcoat borrowed from a tourist standing nearby.

The Post kept printing. The country kept reading. After a week, Agnes Lowe returned to the inn. The crowd waiting for her was as large as the one that had sent her off. She had gained weight during her week in the wilderness. Sixty-four marriage proposals were waiting in the mail. She went to dinner at the Stanley Hotel that night, attended a dance at a nearby lodge, and was welcomed back by the mayor of Estes Park.

She gave talks in Denver. She wrote her own account in the Post, describing how difficult it was to return to civilization.

Then she vanished from the historical record entirely.

What actually happened during that week in the woods came out later, after Horace Albright, the National Park Service's assistant director, heard about the stunt and complained. Superintendent Way admitted it. A ranger had met with Agnes Lowe at regular intervals throughout her week in the park. He brought her regular clothes. He took her to a cabin where she could rest for a couple of days at a time. Way was not apologetic. He had set out to get attention for the park and had done exactly that. Visitation to Rocky Mountain National Park more than doubled in 1917.

Curt Buchholtz, who wrote the definitive history of the park in 1983, tried to find Hazel Eighmy or any of her relatives while researching his book. He found nothing. She had gone back to whatever life she had before Birch handed her a leopard skin and a new name. His conclusion was simple: the only logical reading of the evidence is that the whole thing was staged from the beginning. His only lingering thought was about what became of her.

Enos Mills, the Father of Rocky Mountain National Park, the man who spent a decade arguing that wild places deserved protection because of their honesty, walked a fictional character into the woods and handed her off to a ranger waiting on the other side of the tree line. He wrote afterward that the experience had proven something meaningful to him about human resilience.

He was talking about a woman who had spent the week in a cabin.

Moe set his cup down and looked out toward the mountains for a moment.

"You know what gets me," he said. "It worked." It did. It worked for over a hundred years. We're still talking about it. The mountains out the window looked the same as they always do. Patient. Keeping secrets the way they keep all the others, which is to say, not forever. Just long enough. |